The Art of Words: How Language Shapes, Stifles, and Misleads

A call for linguistic precision in an age of verbal manipulation

"The basic tool for the manipulation of reality is the manipulation of words. If you can control the meaning of words, you can control the people who must use the words." — Philip K. Dick

Consider the difference between calling someone a "climate skeptic" and a "climate denier." Both terms describe a person who questions certain aspects of climate science or policy, yet they paint entirely different pictures in our minds. The skeptic appears thoughtful, methodical (someone who withholds judgment pending further evidence). The denier, meanwhile, seems obstinate, willfully ignorant, even delusional. Same person, same position, but the choice of label predetermines how we receive their arguments before we've even heard them.

This isn't an accident. The words we choose (or more precisely, the words we're encouraged to adopt) carry profound implications for how ideas are received in public discourse. Too often, these terms serve not to clarify but to venerate or vilify, creating linguistic shortcuts that bypass critical thinking entirely. In an era where complex issues demand nuanced discussion, we find ourselves trapped by language that reduces multifaceted positions to moral binaries: you're either with us or against us, enlightened or ignorant, progressive or regressive.

It's time we examined the loaded terms that dominate our conversations and consider their impact on free thought and genuine dialogue. In questioning the language we use, we begin to reclaim the space for honest discourse that our society desperately needs.

The Power of Labels in Shaping Perception

Human beings are pattern-seeking creatures who naturally categorize the world around us. Labels serve a crucial cognitive function—they help us process complex information quickly and efficiently. But this same efficiency can become a liability when labels distort rather than illuminate truth.

Consider the proliferation of "anti-" prefixes in modern discourse. We hear constantly about "anti-vaxxers," "anti-science", and "anti-progress." Each of these terms performs the same sleight of hand: they frame the labeled person as inherently opposed to something universally positive (e.g., health, knowledge, advancement), rather than as someone who might hold legitimate concerns or alternative viewpoints.

Take the term "anti-vaxxer." This label obscures the reality that many so-called "anti-vaxxers" are actually "pro-medical autonomy" advocates or "pro-informed consent" supporters. They may support some vaccines while questioning others, or they may support vaccination in principle for specific interventions, while opposing mandates altogether. But the "anti-" prefix collapses these nuanced positions into a single, seemingly irrational stance against vaccination itself.

Similarly, dismissing someone as "anti-science" for questioning particular scientific claims or methodologies misunderstands the very nature of scientific inquiry. Science progresses precisely through skepticism and questioning. When we label scrutiny as "anti-science," we risk transforming scientific institutions into unquestionable authorities (a transformation that would be, ironically, profoundly anti-scientific). I write more about this here:

Perhaps nowhere is this linguistic manipulation more evident than in the evolution of "conspiracy theorist." Once a relatively neutral term describing someone who suspected coordinated deception, it has become a pejorative weapon designed to discredit inquiry before it begins. The label now implies paranoia, irrationality, and detachment from reality. Yet history offers countless examples of "conspiracy theories" that proved accurate (from Watergate to MKUltra to the Tuskegee experiments).1 When we reflexively dismiss someone as a "conspiracy theorist," we may be shutting down precisely the kind of independent investigation that protects rational society from abuses of power.

These labels function as conversational "stop signs," discouraging nuanced discussion by pre-judging the speaker's credibility or moral standing. They represent a form of linguistic authoritarianism that tells us not just what to think, but how to think about those who disagree.

"The trouble with lying and deceiving is that their efficiency depends entirely upon a clear notion of the truth that the liar and deceiver wishes to hide." — Hannah Arendt

The Misuse of "Anti-Semitism" in Political Discourse

Among the most consequential examples of linguistic weaponization is the misapplication of "anti-Semitism" to silence political criticism. This specific term, which rightfully describes hatred toward Jewish people, has been increasingly deployed to deflect criticism of specific governmental actions and policies.

The problem becomes particularly acute in discussions of Israeli foreign policy. Critics of military actions in Gaza or the West Bank, opponents of settlement expansion, or those outspoken against genocide are immediately labelled "anti-Semitic"—not for expressing prejudice against Jewish people, but for challenging the actions of a nation-state. This conflation of policy criticism with ethnic hatred serves multiple pernicious purposes: it shields controversial policies from scrutiny, it trivializes genuine anti-Semitism, and it silences legitimate political debate.

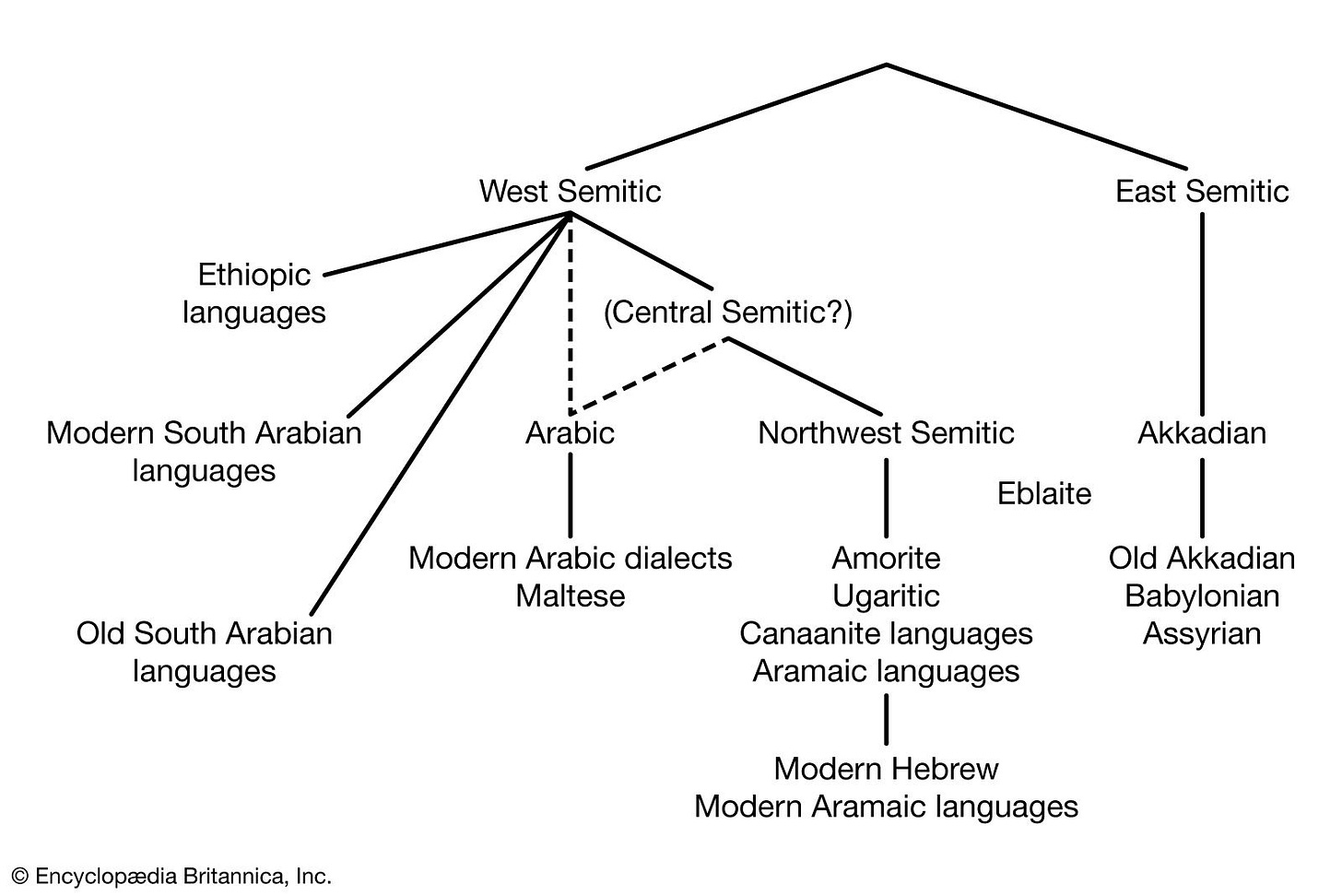

The irony runs deeper when we consider that many of those affected by criticized policies are themselves Semitic peoples. Palestinians, Arabs, and other groups in the region share linguistic and cultural heritage with Jewish populations. Semitic people, or Semites, is a term for an ethnic or cultural group associated with people of the Middle East and the Horn of Africa, including Akkadians, Arabs, Arameans, Canaanites, and Habesha peoples, not just those of Jewish descent. When criticism of policies affecting these populations is labeled "anti-Semitic," the term loses both its precision and its moral clarity.

This isn't to deny the reality of anti-Jewish prejudice, which remains a problem worldwide. Rather, it's to argue for linguistic precision that distinguishes between bigotry against people and criticism of governmental actions. A person who opposes specific military campaigns, war crimes, or diplomatic strategies is not necessarily harboring ethnic hatred any more than someone who criticized American foreign policy during the Iraq War was "anti-Christian" or "anti-American."2 Their position might better be described as a "dissenting voice" or "controversial opinion"; these terms allow for substantive engagement without moral condemnation.

The stakes here extend beyond any single conflict. When emotionally charged terms are weaponized to deflect criticism, we undermine the possibility of informed, rational deliberation about complex geopolitical issues. Citizens must maintain the right to debate their government's actions and their tax dollars' uses without being smeared as bigots for exercising that right.

Contradictions in Terms: The Case of "Unvaccinated"

Some terms reveal their manipulative nature through sheer logical incoherence. Consider "unvaccinated" (a word that has dominated health discourse in recent years). Grammatically, the prefix "un-" typically denotes a reversal of a previous state: we unlock doors that were locked, untie knots that were tied, unwrap gifts that were wrapped. But someone who has never received a particular medical intervention hasn't reversed anything (they've simply maintained their baseline state).

The accurate term would be "non-vaccinated" or "vaccine-free," descriptors that carry no implicit judgment about the rightness or wrongness of that state. But "unvaccinated" does something different: it frames non-compliance as a deficiency, a deviation from a norm that should be corrected. The prefix suggests that vaccination is not just recommended but expected, that choosing differently represents an undoing of proper order.

This linguistic sleight of hand becomes more problematic when we consider debates about the nature of certain medical interventions themselves. If a product functions more like gene therapy or prophylactic treatment than a traditional vaccine, then calling someone "unvaccinated" for refusing it may be doubly misleading. It assumes both that the intervention is properly categorized as vaccination and that declining it represents a departure from normal health maintenance.3 A "vaccine skeptic" or "medical choice advocate" might question these assumptions; their position deserves engagement, not dismissal.

Climate Change: Fact or Fiction?

The broader pattern extends to other contradictory terms that have entered mainstream usage. The term "climate denier" is a linguistic sleight of hand; it implies that skeptics reject the existence of climate itself, which is absurd. In reality, most are labeled as "deniers" and question specific claims (such as the extent of human influence, the accuracy of predictive models, or the efficacy of proposed policies). This mischaracterization flattens nuanced positions into a caricature; it stifles debate. For example, questioning the feasibility of net-zero policies or the economic trade-offs of rapid decarbonization doesn’t equate to denying observable climate shifts. Yet, the term’s emotional weight (evoking Holocaust denial) casts skeptics as morally reprehensible, not just intellectually mistaken. This tactic shuts down discussion by framing dissent as heresy, not reason. The broader pattern of weaponizing language extends to other terms, like "anti-science," which similarly conflates skepticism with ignorance; it obscures legitimate debates about data interpretation or policy priorities.

Abusing the idea of “Hate Speech” as a Tool for Suppression

The label "hate speech" has ballooned to encompass a dangerously vague range of expression; it often sweeps up protected political speech in its net. What began as a shield against targeted harassment or incitement to violence now risks becoming a cudgel to silence dissent. For instance, critiquing immigration policy or cultural trends can be branded as "hate," even when grounded in reasoned arguments or data. This overreach creates a chilling effect; individuals self-censor to avoid social or legal repercussions. The term’s subjectivity (lacking a universal definition) hands disproportionate power to those who wield it; it allows them to dictate what’s acceptable without engaging with the substance of the speech. By framing complex issues as binary (hateful or not), it erases gradations of opinion and intent; it reduces public discourse to a battle of labels rather than ideas.

Language shapes thought, and imprecise language enables imprecise thinking. Terms like "climate denier" and "hate speech" are not just descriptors; they’re tools that frame debates before they begin. By accepting them uncritically, we surrender to frameworks that oversimplify reality and polarize discussion. These terms don’t clarify; they constrain, forcing us into pre-set categories that obscure the messy truth of human perspectives. To reclaim clear thinking, we must challenge the language itself; we must demand precision over propaganda.4

Why Words Matter and How to Reclaim Discourse

The stakes of linguistic manipulation extend far beyond semantics. When loaded terms polarize discussions, they make compromise and mutual understanding nearly impossible. When labels dehumanize opponents, they justify treating disagreement as a moral emergency rather than a normal feature of rational discourse. When imprecise language stifles critical thinking, it undermines the informed citizenship that free societies require.

But recognition of the problem points toward solutions. We can begin to reclaim honest discourse by cultivating habits of linguistic skepticism:

Question labels before adopting them. When someone is described using a loaded term, ask what that person actually believes or advocates. Seek primary sources rather than relying on secondhand characterizations. You may discover that the "anti-science" advocate is actually calling for more rigorous peer review, or that the "conspiracy theorist" is raising legitimate questions about institutional transparency.

Choose precise, neutral language. Instead of "anti-vaxxer," consider "vaccine skeptic," "medical choice advocate," or “evidence-based advocate”. Rather than "climate denier," try "climate policy critic" or "climate science skeptic" (for those scrutinizing data or models). Replace "conspiracy theorist" with "independent investigator," or “narrative skeptic” when someone is asking questions about official narratives. Instead of “hate speech" (when misapplied to political speech), use “dissenting opinion” to reflect disagreement without moral condemnation. Neutral language opens space for substantive engagement with actual positions rather than caricatures.

Recognize the humanity of disagreement. Complex issues generate complex responses. The person who disagrees with you likely has reasons for their position that make sense within their framework of values and experiences. Loaded language makes it easier to dismiss those reasons without examining them, but rational discourse requires the harder work of understanding why reasonable people might reach different conclusions.

Model better practices. Writers, especially those on platforms like Substack, have a particular responsibility for challenging linguistic manipulation. We can demonstrate that it's possible to disagree strongly while still representing opponents fairly. We can show that precision enhances rather than diminishes the power of an argument.

The goal isn't to eliminate all evaluative language or pretend that all positions are equally valid. Some ideas deserve criticism, and some actions warrant moral condemnation. But criticism and condemnation are more effective when they engage with substance rather than rely on linguistic shortcuts that bypass thinking altogether.

Reclaiming Precision in Our Discourse

The terms "anti-," "conspiracy theorist," "anti-Semitism," and "unvaccinated" illustrate a broader pattern of language being weaponized to control rather than clarify discourse. Each represents a different aspect of linguistic manipulation: the creation of false binaries, the pathologizing of dissent, the misapplication of moral categories, and the imposition of loaded frameworks through grammatical sleight of hand.

Yet recognizing these patterns offers hope. Once we see how language shapes our thinking, we can begin to choose our words more carefully. We can insist on precision, seek out primary sources, and resist the pull of labels that make thinking unnecessary. We can reclaim the space for genuine dialogue that rational discourse requires.

I'm reminded of a moment several years ago when I caught myself dismissing someone as a "conspiracy theorist" without actually examining their claims. When I later investigated the specific issues they had raised, I discovered that several of their concerns were grounded in documented facts I had been unaware of. My casual use of the label had prevented me from learning something important about the world.

That experience taught me that our words don't just describe reality (they shape how we engage with it). In an era of information abundance and institutional uncertainty, we need all the tools we can get for making sense of complex issues. Precise, honest language is one of the most important tools we have. It's time we started using it.

What loaded terms have you noticed shaping discourse in your own experience? Share your thoughts in the comments, and suggest alternative phrasings that might foster more productive dialogue.

"If thought corrupts language, language can also corrupt thought." — George Orwell

Like my content?

Support my work with Ko-Fi

Further Reading

On Historical "Conspiracy Theories": Jesse Walker, The United States of Paranoia: A Conspiracy Theory (Harper, 2013); Lance deHaven-Smith, Conspiracy Theory in America (University of Texas Press, 2013)

On Anti-Semitism and Political Discourse: Norman Finkelstein, Beyond Chutzpah: On the Misuse of Anti-Semitism and the Abuse of History (University of California Press, 2005)

On Medical Language and Framing: Arthur Caplan, Smart Mice, Not-So-Smart People: An Interesting and Amusing Guide to Bioethics (Rowman & Littlefield, 2006)

On Language and Thought: George Orwell, "Politics and the English Language" (1946); Noam Chomsky, Manufacturing Consent (Pantheon, 1988); Steven Pinker, The Language Instinct (William Morrow, 1994)

I read this over breakfast, and thoroughly enjoyed it. (And found it quite useful.)

It sparked a thought of the push in 1984 to make a smaller dictionary, flattening out the language. Have you noticed any of that in general discourse? My thesaurus (and dictionary) not only helps me write, but it helps me think. I like the old ones, too. There's a 1973 printing of The Oxford English Dictionary on my shelf. It's one of those two-volume tiny print ones, jam packed with words. I wonder if a gradual movement away from nuance is an eternal trend, and endless inertia to fight. Comparing the First edition of Webster's Dictionary (1951) and the Eleventh Merriam-Webster's (2003), "Interminable" examples move from endless suffering, to "a sermon."